Humorphism in AI Agents

As we design AI-enabled tools for creators, it's worth learning from the past failures—and sudden recent success—of humanistic AI interactions

Remember skeuomorphism? iPhone apps in 2010 were rife with shiny, "lickable" buttons, drop shadows galore, and enough wood grain to panel a 1987 Wagoneer.

Skeuomorphism mimicked the affordances and constraints of physical objects in their digital equivalents, not just to provide a sense of familiarity, but also to help guide users toward expected interaction patterns in this new digital medium.

Now, with the explosion in progress in generative artificial intelligence, we're seeing the realization of "AI agents"—autonomous digital knowledge workers that act on your behalf, taking a high-level goal and running iteratively (often stopping to check in for feedback) until the goal is achieved. These agents have a notable characteristic: they aren't human, but they are often designed to act that way.

Call it "humorphism". And historically, it has sucked.

The disappointment of humanistic digital agents

For years, designers of AI agents and chatbots have been intentionally building in "unnecessary" human characteristics to make the system more comfortable to interact with. Humorphism in an agent's design is intended to induce anthropomorphism in the user—that is, to make you apply human-like attributes to the system. This provides a preexisting set of expectations for how you might interact with the bot, which was precisely the role that skeuomorphism played early in the evolution of digital interface design.

Like skeuomorphism, humorphism emerged from a desire to make digital interactions more accessible and relatable. As bots became more common, designers tried to make them more approachable by incorporating human characteristics, such as names, voices, and even virtual appearances.

Unlike skeuomorphism however, humorphism tended to write checks it couldn't cash. It turned out that encouraging humanistic interactions with extremely limited digital systems was a road to disappointment. The first few generations of humorphic AI systems failed in several interesting ways.

Natural language interface without natural language power

Apple's Siri, Google Assistant, and Amazon's Alexa are probably the most well-known voice-controlled virtual assistants, although it is remarkable how limited their utility has been, given the massive resources behind those three companies.

These agents are supposed to be able to understand and respond to complex sentences. In reality, they are hamstrung by the lack of deep integrations with other systems, not to mention a tendency to misunderstand you.

In addition to natural language (mis)understanding, Microsoft's Cortana attempted to express a more human-like personality through her remarks and demeanor. This didn't save her from being discontinued when it became clear that the underlying use cases just weren't there.

Digitally-embodied avatars living in uncanny valley

In some cases, humorphism extends to the visual representation of AI agents. Virtual avatars or characters are created to give users a tangible, human-like entity to interact with.

Virtual influencers like Lil Miquela and Shudu Gram, powered by AI algorithms, have been designed with realistic human appearances and personalities. These virtual beings engage with users on social media platforms, blurring the line between AI and human interaction.

However, putting a human form to a digital system has the effect of amplifying the uncanny valley experience, creating a set of expectations that are extraordinarily difficult to meet, and leading to disappointment or disgust when there is a disconnect between promise and reality.

(Humanistic avatars have another interesting failure mode, wherein some of their users want to have sex with them. I'd call this more a failure of our own programming than the agent's, but it certainly raises some dystopian prospects.)

Non-humanistic avatars can help avoid some of these challenges. The virtual therapist Woebot avoids humorphism altogether by using a robot cartoon character, creating a more approachable and relatable experience for users seeking mental health support. This helps provide a face for the system without promising a truly human-like interaction.

Full of behavior and gestures, signifying nothing

Humorphism can also involve incorporating human-like behaviors and subtle gestures into digital systems. Since more than half of the content of communication is nonverbal, this approach seemed to make a lot of sense.

SoftBank's humanoid robot Pepper was designed to recognize and respond to human emotions through facial expressions, body language, and voice tone. Pepper's designers hoped that the ability to exhibit human-like behaviors and gestures, such as nodding, waving, or displaying empathetic facial expressions would enhance its relatability and appeal to users.

Some were skeptical. Pepper flopped due to a lack of actual functionality, with The Verge reporting, "Pepper failed at almost every other task assigned and ended up being roughly as sophisticated as the smart speakers that were appearing around the same time."

The new golden age of humorphism

While humorphism in the past was marred by disappointments and unfulfilled promises, the recent advancements in AI technology, especially the emergence of GPT-4, have brought humorphism back to life. The emerging cohort of powerful, context-aware, and knowledgeable AI agents are finally realizing the potential that humorphism has always aimed for, marking the beginning of its golden age.

GPT-4 is arguably the first non-sucky conversational AI. It has enough context and knowledge to provide useful (if not always 100% correct) answers to questions, and is gaining rapid acceptance as an assistant for a wide range of tasks. Today, I see most people treat GPT-4 as a slightly-hallucinatory-yet-somehow-more-useful version of the Google search box—but asking for healthy muffin recipes by typing a question into a webpage chat window is barely the beginning.

The current era generative AI is sparking a humorphic agent revolution, with the promise and dream of near-autonomous operation feeling closer than ever. Tooling for this space like Langchain has rapidly emerged, allowing developers to easily build their own agents on top of generative AI models. These agents not only excel at a wide range of tasks but also facilitate more natural and relatable interactions with users, fulfilling the original vision of humorphism.

As we enter this golden age of humorphism, I expect humanistic AI agents to play an increasingly important role in our lives. The improved capabilities of these agents will foster deeper engagement and trust between humans and AI, allowing users to derive greater value from their interactions.

But this is just one stage in the ongoing evolution of AI design. As users become more familiar with AI-driven interactions and technology continues to advance, we will eventually see a shift towards more efficient and functional AI design patterns. This will mark the gradual decline of humorphism as AI agents prioritize practicality and utility over human-like attributes.

After humorphism: what will be the "flat design" for AI agents?

Skeuomorphism in digital product design was mostly succeeded around 2010 by an interface design approach called "flat" design. Flat design (or "authentically digital", if you've got your marketing shoes on) came about once users became more comfortable with digital interfaces. Interaction patterns settled, and the skeuomorphic supports were slowly removed.

(As an aside, this was an interesting time to be a designer—in the span of a year or so, we went from spending days in Photoshop shaping the reflections and distortions in a mercury thermometer app, to slapping a thin red rectangle and a couple numbers on a screen and yelling "ship it!")

As with skeuomorphism, humorphism will fade away as interaction patterns with AI become more established. As people become increasingly comfortable with AI agents, they'll rely less on human-like characteristics to navigate their interactions. With the decline of humorphism, the interaction design of AI agents is likely to evolve to focus on reducing interaction friction and increasing functional specialization.

Efficient, seamless interactions

As interaction patterns become more established, designers can stop worrying about being "familiar" and focus on creating more seamless ways for users to engage with AI agents.

These new interaction methods could encompass a variety of modalities, such as voice, gesture, or even brain-computer interfaces. AI agents could be designed to respond to pervasive non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions, body language, or even changes in body temperature or heart rate. These more organic and seamless inputs will ultimately reduce the reliance on humanistic communication patterns like natural language conversations.

Task-specific agents

AI interaction design may also shift towards creating task-specific agents, where each agent is designed to excel at a particular task or domain. This specialization allows for the agent's performance to be tuned to a small set of success criteria, catering to a set of specific needs and requirements without getting distracted or accidentally falling in love with you.

Specialized AI agents could be developed for medical diagnostics, financial analysis, or even niche hobbies such as birdwatching. There may also be specialized agents intended to represent the interests of you as an individual—your very own Ari Gold who will fight for you on a digital battlefield to make sure other agents aren't able to take advantage of you.

Design for humorphism now... but not for ever

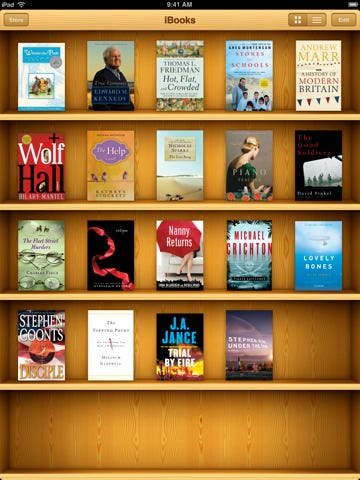

As designers, we have to think not just about how our products will be used today, but also how they will fit into the landscape in the future. As you design for AI-enabled digital products, feel free to embrace the new golden age of humorphism—but be careful not to forget that there will soon be a day where your reliance on human-like interaction patterns will be looked at the same way as the honeyed oak bookshelf in the background of Apple's 2010 iBooks app.

Instead, think expansively about different experiences enabled by the underlying generative AI technology, and look for opportunities to make your interactions more efficient, pervasive, seamless, and specialized. Anticipate new technologies and user expectations. This space is moving fast, and it will be all too easy to design for a world that, when your product launches, has already passed us by. I’m trying to take my own advice into account as I design creator tools like Salesforce’s Einstein GPT for Developers, and it’s challenging to not fall into the same predictable patterns and approaches.

It's not new advice, really. But it's all moving at goddamn close to light speed right now, so you can wait until things slow down—or you can try to help make the future.