"Design", if you're fancy enough to look it up in the dictionary, means the process of planning the form and structure of objects or systems, usually around a set of constraints and goals. This definition is too broad to do anything useful with, and also nearly made me fall asleep, so let's make up our own.

To start, let's limit the meaning of "design" to the process of creating things around the needs, wants, and capabilities of a human being. This is sometimes called "human-centered design" or "user experience design"—and if you're old school, "ergonomics" (say what you want about people in the mid 20th century, but they gave things awesome names).

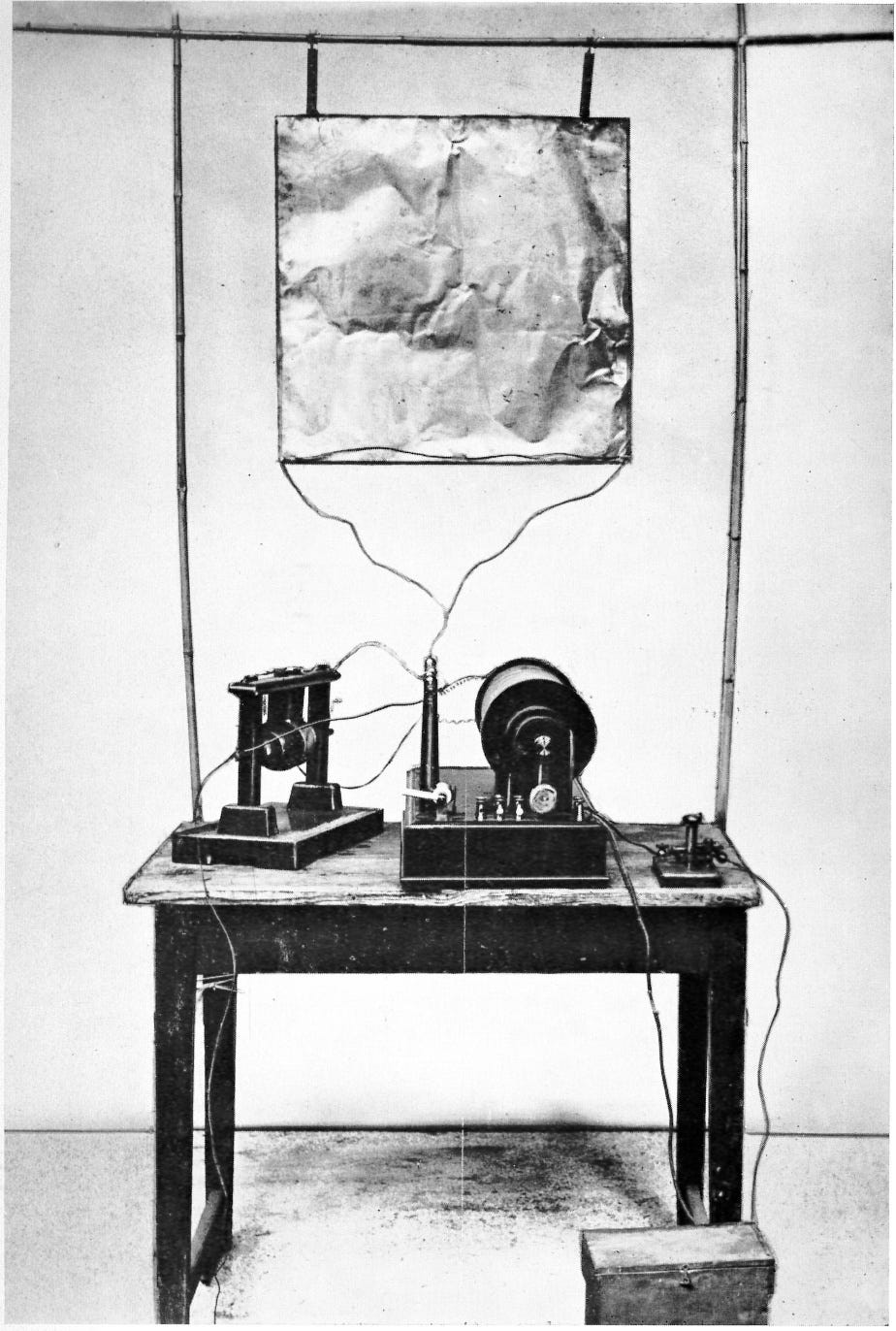

Design also is distinct from invention, in that invention means developing a whole new ability, like sending information through the air on invisible waves, whereas design is the arranging of existing inventions into something that takes the human side into account. Inventing the radio is different from designing a radio. Invention gets you Marconi's first wireless telegraph transmitter. Design gets you Dieter Rams' RT20.

Let's move on to "creative".

"Creative" refers to the act of creation. Building something from nothing—or more commonly for us non-deities, from a set of simpler primitives and components. A composer creates music from notes and timing. A painter creates a scene from pigments and medium.

Let's separate the act of "creation" from the idea of "creativity". Ultimately, creation must generate artifacts, whether they are ephemeral (a song) or concrete (a painting). It doesn't actually matter if the song is derivative, or if the painting is cliché; creation can happen in the absence of "creativity", and some critics might say it usually does.

Finally, let’s define "tools". This felt like an easy one when I was getting started, but in the end a tool can be a lot of things, many of which don't look very tool-y.

Take oil painting (and you will a lot, if you stick around). Is a paintbrush a tool? Yes, pretty obviously. Are paints a tool? A canvas? I think yes—they enable the act of creation together, and the results would be noticeably different if one or more were missing. In fact, thinking about tools metaphorically as "brushes", "paints", and "canvases" is a helpful way of organizing our thoughts around what makes something a creative tool in the first place. But we'll come back to that.

So "designing creative tools", in the least succinct way possible, is the design of tools that help others to engage in the act of creation, with a specific focus on how these tools will be understood and employed by their users. From DJ booths and chef's knives to point-and-click user interfaces for building complex web-based automation flows, the tools we give creators have a great influence on what they can make us.

An aside: why is this web guy all about oil painting metaphors?

Like my awkward taste for world music involving didgeridoos, it goes back to my childhood. Cue hazy TV show memory sequence.

My dad's parents came to art relatively late in life—my grandmother picked up oil paints in her middle age, and my grandfather began wood carving a few years later. Not the typical starving artist immigrants, they had built comfortable lives for themselves in Franklin Lakes, New Jersey before indulging their creative sides.

My memories of their home are filled with the light, sweet stink of turpentine and mineral oil. Down in their fluorescent-lit basement, I loved how the brushes and chisels and palette knives and gouges politely cohabitated, the carving tools in my grandfather's worn but impeccably clean workshop, and the paints in my grandmother's wild studio.

My grandfather died, too young, and his tools sat untouched. I visited them sometimes, shuffling through piles of project wood and 1980s electronic equipment to stand in the workshop alone and survey the wooden-handled implements all hanging in size order on the pegboard. I tried to carve something once, probably an ashtray (nobody smoked), but I slipped and sliced a nice chunk out of my hand. Wood carving took a kind of measure-twice-cut-once-ness that I never really could get my mind around.

My grandmother kept painting: portraits, still lifes, landscapes. She traveled to faraway places, almost always to paint, or to buy books about painting from little shops in little towns, or to teach others how to see light in ways that would let them make something beautiful.

Later, when her cancer treatments failed, they switched her to prednisone. It puffed up her face, but gave her an explosive energy in the final months of her life. She produced dozens of canvases, none worked quite to completion but all demonstrating a hurried intensity, like she didn't want to take a single idea with her.

When she died, my dad got the carving tools, but all the oil painting paraphernalia became mine. Most of the brushes were gummy or fraying (at the end she must not have paused for her usual cleaning and conditioning with Speedball Pink Soap), but a single stiff No. 6 hogshair meant more to me than anything I could buy at Glick. I've held onto these for two decades now, though my oils practice never really became a habit no matter how much I called myself a "painter".

Instead, I turned to the digital world. Code and pixels felt as real as paints to me, and have the distinct advantage of being easier to clean off your hands.

Brush, paint, canvas

Back to that metaphor I promised/warned about.

I like to think about three types of tools coming together in the act of creation: the brush, the paint, and the canvas.

The "brush" enhances the capabilities of the creator, changing not just what their hands can do, but what their eyes can see, and what their mind can think. Brushes include things like syntax highlighting in the coder's IDE, the pen tool in the graphic designer's vector editor, and the venerable seam ripper in the quilter's arsenal (yeah, I'm going to keep coming back to the seam ripper).

The "paint" is the creative medium, the raw materials that will be brought together. These can be raw indeed—words for the writer, or black walnut wood for my grandfather—but can also represent larger components of encapsulated complexity, like an intricate rubber stamp, or a whole damn programming language. These prebuilt components incorporate the craftsmanship of others into your own creations, letting you build upon those foundations to create more complex works.

The "canvas" is the workspace, where the medium is blended, layered, and worked. It holds the creation in front of the creator, letting you see where you missed a spot. Some canvases are easy to identify: a word processor's page, or an audio editor's spectrogram. Others you need to squint a bit: the canvas of a piece of performed music is wholly intangible, and the canvas of a crocheted sweater is the knitter's knees and sofa arm and coffee table—at least while they're knitting.

But why organize things into a metaphor in the first place? Does calling code syntax highlighting a "brush" really buy us anything? Hopefully, yes; the goal of this project isn't just to talk about creative tools in isolation, but to draw out common patterns and features that work in different contexts. I hope to find parallels that can help the designer of a code editor learn from the designer of a 3D printer, and vice versa. By organizing our thinking like this, we increase our chances of finding unseen connections and learning something really deeply true about what it means to design tools for creators.

Stay tuned and subscribe to hear from some people who are doing that design work every day. I hope you learn as much as I do.

~ Geordie